Discover our Special Issue – MAG Hors-Série on Visual Impairment

Read the accessible version for people with low vision

Listen to the audio version for people who are blind

What is visual impairment?The World Health Organization (WHO) defines visual impairment as visual acuity of less than 3/10 after optical correction and/or a visual field of less than 10 degrees.

French legislation defines a person as blind when visual acuity is less than 1/20.

Visual impairment—and visual disability or multiple visual disabilities—may also result from:

- oculomotor disorders,

- impaired perception of colors, contrasts, and depth,

- variations in visual ability depending on lighting conditions, the use of glasses, or fatigue.

The WHO is currently working on a new classification (ICD-11) that will integrate these factors. In addition, an individual’s use of visual abilities depends on their personal history, prior visual experience, other skills (such as cognitive or motor abilities), and even identical pathologies or levels of severity may lead to very different difficulties in daily life.

Finally, these criteria are very difficult to assess in very young children or in people with significant cognitive disabilities, for whom evaluating the severity of visual impairment requires the expertise of specially trained professionals.

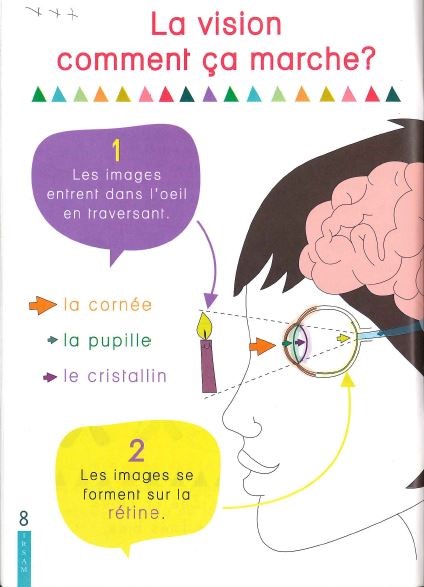

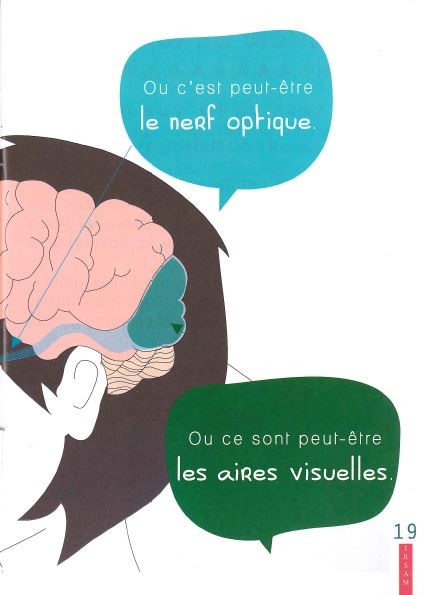

Visual impairment may result from a congenital or acquired malformation or disease, or from an accident affecting one of the components of the eye, the optic nerve, or the brain.

When the visual system is affected, several associated symptoms may occur: eye pain, headaches, fatigue, attention and concentration difficulties, and loss of concentration.

Functional consequences are multiple:

- seeing very blurred images,

- poor color perception,

- extreme sensitivity to light,

- inability to see in low-light conditions,

- seeing only part of the surrounding environment.

This explains the complexity of understanding exactly what a visually impaired person perceives.

Vision is the most immediate means of accessing the external world; it is global and instantaneous.

It is estimated that 80% of external information comes through the visual channel.

The mental representation of our environment built from impaired vision may be partial or distorted.

1. Blurred vision

- Depending on visual acuity, the environment may appear as if seen through frosted glass, populated by shadows and light, with poorly defined shapes and little contrast..

- The presence of an overly strong light source can be blinding. The visual scene becomes faded, with few identifiable elements.

When peripheral vision is preserved, the environment is still perceived globally, allowing the person to orient themselves.

2. Visual field impairment: age-related macular degeneration, certain optic nerve disorders…

Damage to central vision leads to a decrease in visual acuity. Details become difficult or impossible to perceive, and photophobia may occur. Color and contrast perception may be altered. Fine exploration of objects becomes challenging, and reading is disrupted.

3. Peripheral vision impairment (glaucoma, certain forms of retinitis pigmentosa…)

Perceiving an object as a whole becomes increasingly difficult when the object is large. The person faces a fragmented environment that must be mentally reconstructed. Significant cognitive effort is required to relate elements to one another. Reading may sometimes be preserved. In low-light conditions, visual abilities are strongly reduced.

Compensation professionals

Addressing visual impairment involves specialized professionals such as orthoptists, mobility instructors, daily living skills instructors, occupational therapists, specialized teachers, and document transcribers and adapters.

Rehabilitation interventions cannot be isolated or simply combined, as they target overlapping areas and share common objectives.

Depending on individual needs, the multidisciplinary team defines what is required for comprehensive care, implementing methods specific to each discipline.

1. The orthoptist, in collaboration with the ophthalmologist

Assesses the visual deficit and develops a rehabilitation plan based on the objectives of the individual care plan.

- The ophthalmologist treats the condition, prescribes glasses if needed, and provides information on the pathology and its expected progression.

- The orthoptist specifies the functional consequences of the conditions: perception of colors, contrasts, depth, and distances; ability to use vision in different gaze positions; and the use of vision for communication, mobility, analysis, and environmental recognition.

- They stimulate ocular motility and optimize residual vision while taking the visual field into account.

- They improve visuomotor coordination to facilitate movement and fine motor activities such as writing.

- In collaboration with the optician, they recommend necessary adaptations: reading stands or ergonomic desks, lighting, font type and size, optical aids (magnifier), and positioning of the student in the educational environment.

2. The occupational therapist

Relies on the orthoptist’s evaluations to work on spatial skills and support gesture adaptation.

- Develops manipulation, exploration, and object-analysis skills to enable visually impaired individuals to act more independently in their environment.

- Guides the individual in discovering strategies that improve daily-life efficiency.

- Aims to reduce obstacles to activity by suggesting material or environmental adaptations that facilitate successful performance.

3. The daily living skills instructor (AVJ specialist)

Works closely with the occupational therapist.

- Specialist in daily living autonomy, focusing on developing functional and practical skills.

- Helps visually impaired individuals gain concrete independence in daily life: washing, dressing, orientation, and organizing their living space.

4. The mobility instructor

After assessing abilities and needs, teaches visually impaired individuals compensatory, safe, and autonomous mobility techniques.

- Supports discovery and understanding of the environment.

- Facilitates the acquisition of guiding techniques, protection methods, and cane use to move safely and avoid obstacles.

- Develops observation skills through functional vision and sensory and cognitive compensations.

- Supports autonomy in walking and using public transportation.

More information: technique-quide.ideance.net

5. The psychomotor therapist

Provides sensorimotor experiences that help visually impaired individuals to:

- Discover and engage with their body and adapt to their environment.

- Explore and develop visual and multi-sensory potential.

- Develop compensatory strategies for visual impairment.

6. The specialized teacher

Provides expertise in compensatory techniques:

- Teaching Braille and specialized materials.

- Learning adapted computer tools.

- Methods for exploring adapted documents.

- Developing methodologies to improve efficiency and autonomy in schoolwork.

- Informing partners about visual difficulties and their impact on learning.

- Advising on classroom positioning, adapted workstations, and specialized materials.

- Collaborating with transcribers to make documents accessible.

7. Transcribers and adaptation specialists

Adapt all materials: Braille or large-print documents, maps, plans, and tactile diagrams.

All professionals working with visually impaired children rely on these foundations to support and adjust their interventions.

Glossary

Lexique.pdf (2577 downloads )